Book Review: Blessings and Disasters: A Story of Alabama by Alexis Okeowo

BOOK REVIEW

‘North Alabama was full of Liquor Interests, Big Mules, steel companies, Republicans, professors, and other persons of no background.’

―Harper Lee, To Kill A Mockingbird

To Be Black and Nigerian in the American Deep South

Courtesy of Elle Magazine

Alexis Okeowo is a New Yorker staff writer, journalist, and PEN award winner. She is the daughter of Nigerian immigrants, was born and raised Alabama state capital Montgomery.

In Blessings And Disasters: A Story of Alabama, Okeowo weaves a vivid narrative of Alabama, showing its nuances, revealing what lies beyond stereotypes that range from low education standards to ideological hegemony. The book is equal parts historical narration and memoir, and serves as an intimate response to the question: ‘What is it like growing up as a black person in Alabama?’ — a question that the writer encountered often as an undergraduate student at Ivy League Princeton University.

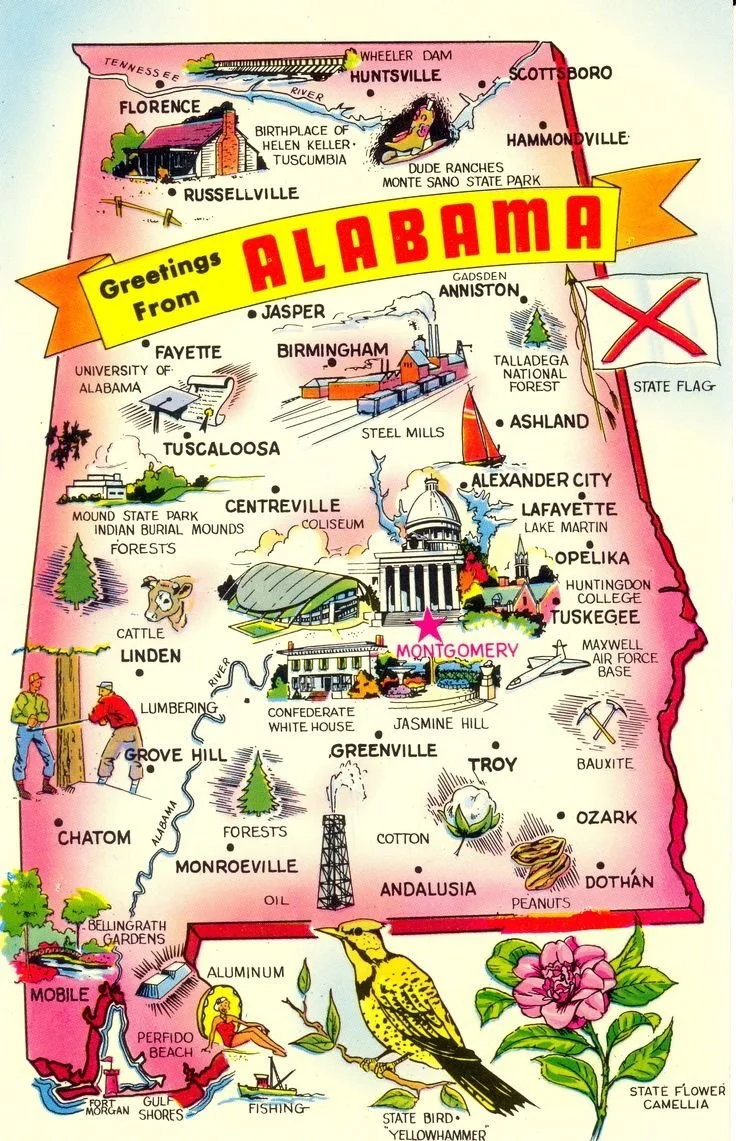

Sweet Home Alabama

Alabama, a southern state known for its racist politics and historically conservative leanings, is perceived as a hostile, unwelcoming state for black, indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC). It is therefore no surprise that when Okoewo left the south to attend an elite university on the East Coast, a place with more progressive proclivities, people were mystified by Okoewo’s recounts of the state. It indeed must have been a curious thing that a black, Nigerian-American daughter of immigrants did not rush to disparage and layout all the shortcomings of Alabama. Instead speaking of the state as home: a place you can't help feel nostalgic about despite it’s shortfalls.

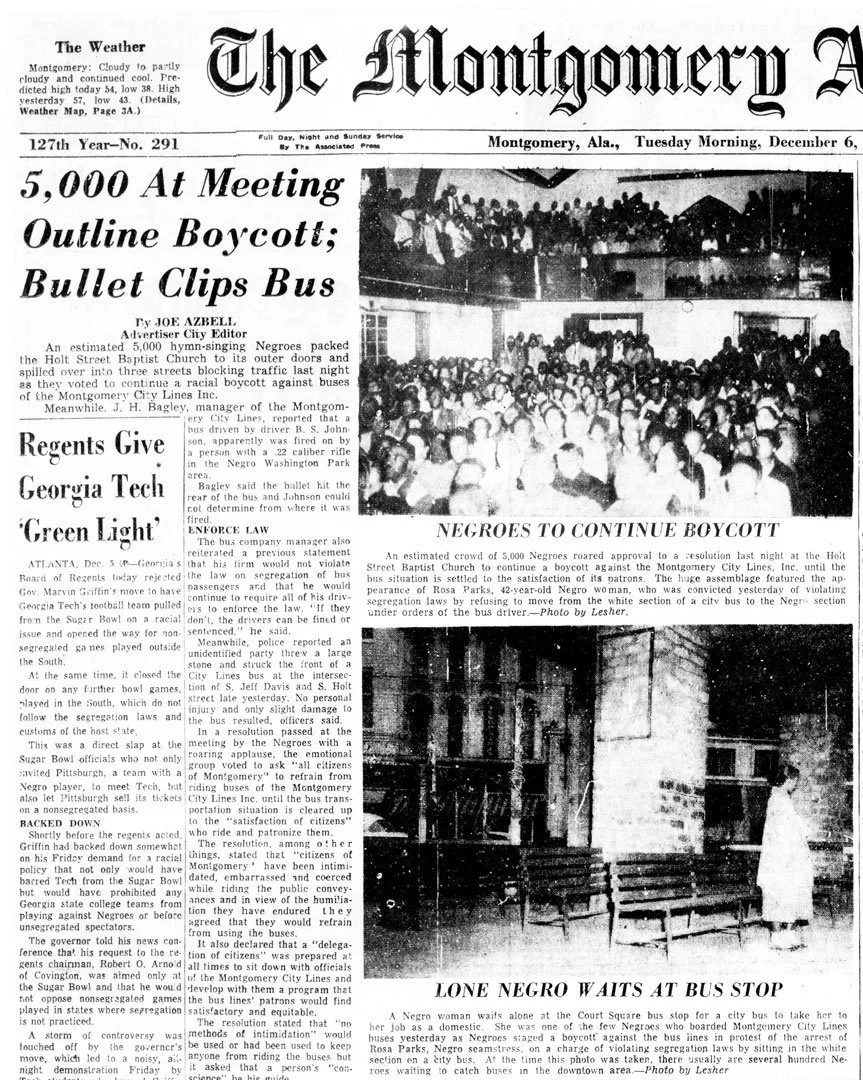

The book’s opening line ‘It depends on who is doing the looking’, serves as the foundation to the author’s response. Outsiders looking at Alabama will have preconceived notions, only seeing the state for its stereotype: a place of rampant racism and white supremacist. Okoewo does not, however, dismiss these stereotypes of the state. Alabama, which is one of the poorest states in the United States of America, has its fair share of problems. After all, these stereotypes are rooted in a lived reality of many Alabamians. The state has historically inspired several civil rights actions such as Rosa Parks’ famous protest in refusing to vacate a segregated part of the bus. Inspiring many scholars and writers such as Harper Lee and Angela Davis to highlight the grave injustices of Alabama.

Okoewo understands and acknowledges the abhorrent history, how it has shaped the state’s contentious reputation, which informs her approach to a modern reframing. The Black experience in Alabama cannot be pigeonholed. Okoewo shows narratives peddled by non-natives, do not entirely reflect her own first hand experience. She sees a state that has its “blessings and disasters”: a state that certainly has shortfalls, but also undoubtedly has merits.

“Alabama is a place that is defined by a certain telling of its history, by its extremes, and by what I see is an oversimplified telling of what’s happened there.

Despite all the state’s faults, I didn’t recognize that version of it—that version that was being held up as the butt of the joke or the source of the country’s ills.”

Rebuttals & Reflections

Blessings and Disasters goes beyond memoir and history: it is also a lesson in how history is sold, whose experiences we centre, and the effects therein. Okoewo denounces the polarising outlook of Alabama. Reflecting on her relatively normal childhood that was not dominated by these ‘extremes’ - a childhood that closely mirrored a typical American upbringing. Leaving the state made her reconsider this upbringing, Okeowo wrote for Elle Magazine:‘…over time, I began to forget parts of how I had grown up, the nuances of how Alabamians lived and thought, and could recall only broad strokes about race and politics and religion. I began to forget that Alabama is, before anything else, home.’ Further highlighting the disparity between how the story of Alabama is packaged to the outside world and the lived experiences of the people residing in the state.

Montgomery Advertiser, 6 December 1955 © Montgomery Advertiser

Okoewo writes about her home state with great care and nostalgia, but resists any impulse toward romanticisation. The book acknowledges the stereotypes of Alabama: religious hegemony, racial tension and political conservatism,providing a historical context rooted in (as she puts it) “Indian removal, the slave trade, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow.” While these are the dominant narratives about the state, Okoewo brings in the underrepresented tales of hope and resilience, of flourishing despite regressive subjugation. These are some of the titular ‘Blessings’ in the state of Alabama. One prominent narrative is of the Poarch Creek people, a tribe of indigenous people who are ‘descendants of a segment of the original Creek Nation, which once covered almost all of Alabama and Georgia’, and who have managed to build a chain of thriving casinos in Alabama, in spite of centuries of displacement and hostility at the hands of the white settlers.

In Blessings and Disasters, Okoewo takes the reader on a journey that unveils the intricacies and complexities. She conducted a series of interviews with Alabamans who provided historical insights and underrepresented perspectives. For example Lewis Calvin Chappelle IV, the Museum Director of the Confederate Memorial Park who provided personal insight on the legacy of the Confederacy. Or Stephanie Bryan, the Poarch Creek tribe’s first female leader, gave insight on the tribes contemporary plights and endeavours. Through these perspectives, Okoewo adeptly reveals what it means to be a black Alabaman, a native person in the state, an immigrant, a white descendent of the confederacy or rural farmer.

Okoewo does not handle Alabama’s history with self-righteous detachment. She instead balances narratives, highlighting the racial disparity. One such example is when she points out the difference in funding for memorial places meant to chronicle the history of Alabama, observing that the ‘Confederate Memorial Park kept running because of more than half a million in state funds. Meanwhile, Black spaces like the Safe House Black History Museum, in Greensboro, which told a story of rural civil rights activism, fought to stay open.’

It is evident that Okoewo deeply cares about Alabama, writing about the problems plaguing the state with great distress. When considering the the effects of climate change she remarks: ‘The increasing occurrence of thunderstorms and hurricanes in a state used to witnessing them, but not at this climate change–induced scale, knocks down and damages trees that then become nests for the pine beetles. But these are smaller disasters.’ These ‘smaller disasters’ are a symptom of the larger systemic issues that have been embedded in Alabama since its conquest by white settlers in the 16th century.

Ultimately, Blessings and Disasters is a tapestry of Alabama’s overlooked stories. It blends the stories of the Creek people, enslaved and formerly enslaved communities, immigrants, and those who carry the burden of history. In a conversation with NPR, an American media Organisation, Okeowo highlighted what she sought to achieve in her book, saying the following: ‘I wanted to tell an alternate history of the state. I wanted to talk about the things that are left out of the state’s story and the experiences of people who decide to stay there, despite so many people writing Alabama off.’ The book triumphs in this regard, giving readers a version of Alabama rarely seen by outsiders.

Blessings and Disasters is conclusively a good history lesson and an enjoyable memoir. It speaks to individuals who hail from places that are dominated, and often marred by their cliches. African readers, who are familiar with ignorant, uninformed conversations that erase their backgrounds would relate to Okoewo’s desire to prove the complexities of her home state. It is also short, digestible and fit for anyone who has ever taken a keen interest in the true nature of Alabama and how its people co-exist.

Thank you to Henry Holt & Company for providing Harare Book Club with a reviewer’s copy via NetGalley.

Written by - Kupakwashe Mabulala